By Fiona Ward

Designer Alice Robinson admits that when she first began working in fashion, she hadn’t given much thought to the origins of the materials she was working with. During her student days studying womenswear, cost was always the main consideration.

“I enjoyed the creative challenge of working from the limited resources in front of me, letting them influence the texture and silhouette of the garments,” she says. “So in that sense, I have always been interested in materials and how they’ve been produced – but I had not confronted the issues surrounding traceability until I worked with leather.”

It was Alice’s master’s degree at the Royal College of Art that piqued her interest in accessories and, consequently, leather – and so began a career dedicated to connecting farming and fashion. ‘Sheep 11458’, her final collection at RCA, was where her journey with traceability started. Having grown up in rural Shropshire, she had an awareness of small-scale animal agriculture and meat production – but on closer inspection, she realised the leather industry had little to do with the local farming standards she was used to.

“I went to all the leather merchants I could find in London to see how much information I could get beyond just where the hides had been tanned. I had really, really vague answers and nothing that led me back to farming practices or dynamics of the people behind the rearing of the animals or the animals themselves,” she says.

The idea for ‘Sheep 11458’ – and later, ‘Bullock 374’ – was born. For both collections, Alice purchased an animal and followed its process – from farming to abattoir, to tanning, material and production into leather goods. Her 2023 book, ‘Field, Fork, Fashion: Bullock 374 and a Designer’s Journey to Find a Future for Leather‘ documents the process of her most recent collection.

Alice’s work led her to meet food and agriculture expert Sara Grady, to whom she was introduced via a mutual friend – and discovered they shared the same concerns about the traceability of leather and ethical farming practices. Together the pair have since launched British Pasture Leather, a new supplier of leather made from the hides of cattle raised on regenerative farms in the UK.

Here, Alice and Sara discuss their aims for the future with British Pasture Leather, and why the continuing conversation surrounding leather traceability is essential…

RLSD: Alice – when did your fascination with leather begin?

Alice: Moving from womenswear and into accessory design for my MA degree was the first time I really looked at leather differently. I’d not designed bags before, and never owned a designer bag myself. I became really interested in studying them, so that it could inform my own work. I found that everything that was deemed ‘fashion’ was highly finished, smooth, blemish-less… perfection. Brand names were all embossed in the leather, giving those items a sense of gravitas. I found this message of superiority and value at odds with the lack of information I could find regarding the provenance of the leather material. Where had the animal lived, what had the welfare been, both of the animal but also the community which had produced the food? Learning more about the globalisation of the leather trade, I became aware of how disconnected the material is from its farm origins. The dominant narrative attached to leather is that the raw materials used to make it are ‘waste’ products, anonymous because the value is determined solely by its capacity to make a desired finished material. I became interested in exploring our perception of leather’s value, based on its provenance beyond a brand name.

RLSD: Why do you think leather piqued your interest?

Alice: For many reasons. Having grown up in Shropshire, the daughter of a farm vet and in a rural farmed landscape, I felt as though I knew a place to which leather is inherently connected. The material is synonymous with luxury and craft. It is emotive. Both in the sense that it’s the skin of an animal, but also because it has a familiarity to it. Perhaps because ever since early human civilisations learned how to preserve and transform hides and skins, we have worn, carried, sat on, smelled and utilised them. I also found branding the material as a waste produced by the meat industry intriguing. I wanted to be intentional about what material choices I was making to create clothing or accessories, and for me that meant acknowledging a hide as a resource coming from a farm – and understanding why and how that had been produced was important. That knowledge would influence my design decisions. The material’s link to food production and land use gave me an understanding of the connection between fashion and farming.

RLSD: Your collection 374 is documented in your book. What were the most surprising things you learnt from tracing your leather from animal to finished product?

Alice: Bullock 374 was a Longhorn Limousin cross. Much like wool, the breed, age and environment in which the animal had lived had influenced characteristics of the finished leather. The thickness, density and volume of it were all predetermined. Different types of animal hides and skins produce different types of leather – so I was surprised to find that certain design decisions were made for me by using this specific leather coming from Bullock 374. It wouldn’t be suitable for making certain items, like a soft leather jacket, and I could no longer make design decisions without considering the limited resources I had to work with.

I also found myself to be forgiving of what are typically called ‘defects’ or ‘flaws’ on the surface of the leather: bug bites, scratches and the like. Knowing how Bullock 374 had lived at Charity Farm gave those marks context. It was liberating to work with a parameter, a boundary.

RLSD: Tell us about your tanning choices on your leathers – did you tan in the UK? What’s the most sustainable way to tan leather in your opinion?

Alice: Yes, the leather for Collection 374 was produced by two tanneries, Holmes Halls in Hull and Pittards in Yeovil, which sadly has since closed. I’d begun the work by looking for a UK tannery which offered a vegetable tanning process. My desire was to create leather by working with existing leather manufacturers in the UK and to learn more about the historic infrastructure we have here. I’d looked to use a vegetable tanning process because I wanted to keep the leather as lightly treated as possible, and the patina and colour of vegetable-tanned leather would lend itself to this. The ideal was to create a leather which would biodegrade and not leave toxicity at the end of life. Unfortunately, during the week I began working on Collection 374 two tanneries which could offer that process closed – and due to the complexity of working with just one hide, my third and final option also couldn’t work with me. This meant I took the hide of Bullock 374 to Holmes Halls, a historic facility producing wet-blue part processed leather, using a chrome tanning method (used in the production of around 85-90% of all leather globally). It was frustrating not to be able to produce the leather exactly how I wanted, but the reality was that it wasn’t possible to do so. The finished leather was minimally finished with a natural wax – I’d chosen not to coat the leather with any synthetic materials to hide scratches or marks. The whole process ended up being an incredibly informative part of the project for me.

My personal view is that the most sustainable way to tan leather is by using ingredients which will result in a material that can biodegrade without leaving toxicity at the end of its usable life. Ideally this can be produced as locally as possible, to the farms and users of the end material.

RLSD: What have been the main challenges you’ve come across while sharing your mission on leather production?

Alice: Infrastructure. I think whether coming from a brand, designer or leather industry perspective, we can share what an ideal method of production could look like. But the reality is that in the UK we have lost much of our historic tanning infrastructure. We’ve also come to learn that leather can be cheap and abundant. The volume of hides produced globally far exceeds the global desire for finished leather and is leading to hides ending up in landfill. When I’d gone to collect the hide of Bullock 374 from the abattoir, I learnt that it would not have been entering the leather supply chain and instead would have been disposed of, if I were not retrieving and using it.

I think one of the main challenges is that leather has become a ubiquitous and anonymous material, often justifiably and unavoidably associated with industrial agriculture and the detrimental effects of that farming system. Feelings about the material are deeply entrenched and in my opinion are the result of consistently being labelled as an anonymous bi-product of the meat industry. I’d like to move beyond that to view the materials we use in fashion and design practice as a reflection of the positive direction of travel the world is going in. Part of our mission with British Pasture Leather is to redefine leather as an agricultural product, and an enduring emblem of the positive impact an animal has had on the land, and therefore a resource to value.

RLSD: Tell us about British Pasture Leather -– how does it work?

Sara: British Pasture Leather is a new supply of leather made from the hides of cattle raised on regenerative farms in the UK.

We created British Pasture Leather so that designers as well as users of leather goods can have the opportunity to choose material and products that originate in local landscapes – and farming practices which improve the welfare of animals, ecosystems, and communities.

We begin by sourcing hides from cattle raised on agroecological farms, whose practices have myriad benefits including: soil carbon sequestration, biodiversity, land stewardship, animal welfare and resilient ecosystems. We identify our source farms through our partnership with Pasture for Life, a farmer-led organisation that “champions the restorative power of grazing” by certifying farms that graze cattle on 100% pasture. These farmers are amongst the most progressive in the UK, a majority of them also hold other certifications, like organic, and, through their like-minded community, they are collaborating to help others along the regenerative path.

RLSD: What is regenerative farming?

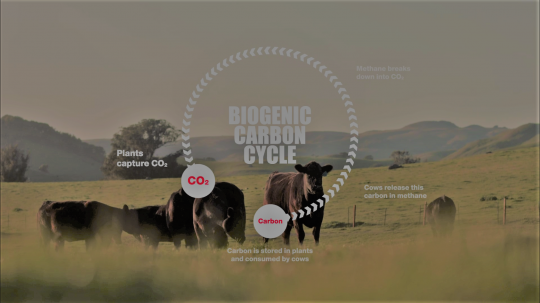

Sara: In laymen’s terms, regenerative farming describes agricultural practices that improve natural systems. It is a response to the detrimental effects of industrial, intensive, chemical-dependent farming methods that have contributed to biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and a host of other negative impacts. On the other hand, what’s exciting to see and to learn is that farming can in fact repair and improve land and ecosystems. That is what is meant by “regenerative.” And from our perspective in working with leather, what’s crucial to the story is that in regions like the UK which grow grass well, grazing cattle are essential partners in the stewardship of landscapes – their impact in a regeneratively managed system is in fact a positive one, they improve soils, which in turn supports biodiversity and all ecosystem functions. And of course, this is all in the context of producing nutritious, delicious food and supporting rural economies.

The deeper mission of our business is to support a broader cultural and economic shift to regenerative and circular practices – and we intend to bring value and recognition to farms whose practices sequester carbon (through grazing), preserve and increase biodiversity, enhance soils, and protect ecosystems. In the conventional supply chain, farmers see no value or payment for hides, because hides are sold by abattoirs. We are of course paying the abattoir for the hides we source, but we are attempting to build a business model that additionally recognises the farmers – because it is their work, on the ground, that delivers the regenerative outcomes which form part of the intangible value of British Pasture Leather. We have been inspired to do this because we have experienced first hand the positive impacts of these farms in the form of thriving animals, soils, and ecosystems, as well as delicious and nutritious food, and also personal and community wellbeing.

Given leather’s evocative qualities, it has a potent opportunity to serve as a means of reconnection between fashion and nature – and advance a much-needed understanding of the good that can be done by farmers who farm in harmony with nature.

RLSD: How is British Pasture Leather produced?

Alice: We have established close collaborative relationships with abattoirs and hide collectors to ensure the traceability of the hides coming from our source farms – and for the tanning and finishing of British Pasture Leather we are working mainly with two facilities. We made a commitment early on in our venture to produce in the UK and to use a vegetable tanning method. This has given us the opportunity to work with one of the last remaining traditional pit tanneries in Britain, providing us with a strong and versatile base material for us to work with. At the finishing stage, we’re working with a family run multi-generational business whose collective expertise spans decades. This knowledge has helped us determine leather qualities that are suitable to a range of design applications including footwear, accessories and interiors. At each stage we have closely considered the sustainability implications of our decisions, opting for low intervention methods of finishing which express the natural character of the hides we use. We have collaborated closely with our production partners over the last three years to make this supply a reality and we now feel confident in the beautiful quality of the leather we’ve produced – it is very exciting to see it entering the hands of brands and studios.

RLSD: Do you see big designers and brands moving across to traceable leather in the future? How do you envision big change?

Alice: I do envision change. Projects like British Pasture Leather are cropping up in America and Europe too. There is a growing interest at a customer level to know where materials come from and how they’ve been produced. I believe this will grow when information can become accessible, engaging and educational. New value chains can only be created though if there is a willingness from brands to adapt and adopt.

Sara: I believe that brands and designers will increasingly be required to demonstrate accountability for the impacts of their material choices. I relate to this personally through my own experience and desires to understand the origins and impacts of things that I purchase and consume: food, clothing, and other material goods. And I think this sense of responsibility is increasingly taking root in people’s purchasing decisions, and therefore will increasingly become part of how things are designed and made.

One of the most interesting aspects of the work we are doing with British Pasture Leather is the sense of “pulling back the curtain” on a material that is not widely or well understood. Sure, we all have leather in our lives. But how often have we had the chance to really understand where it came from and how it was made – and how those aspects might have a deeper meaning?

In the case of British Pasture Leather, we are asking designers and users of leather goods to reshape their perception of this material by bringing its intangible values to the foreground: to recognise the fact that this material is intimately linked to land stewardship and food systems, which ties it to a range of broader impacts.

To encourage brands to adopt British Pasture Leather, we have to foster a special relationship with product and development teams, in which we provide insights that go much further than a typical supplier relationship – we can link product development all the way back to the farm level, and give information about the material’s origins and production in a way that can inform design and product development with new, deeper perspectives.

RLSD: Have you got any exciting projects coming up you can tell us about?

Alice: Just last week we launched our first collaboration with pioneering British leather brand Billy Tannery, in the form of a crossbody bag made from their deer suede and our cattle leather. And, in the coming months we hope to announce more products entering the marketplace made with our leather. Our website will also soon be launching too, so stay tuned for announcements on how to purchase our new styles of British Pasture Leather!

Follow updates of Alice and Sara’s work with British Pasture Leather on Instagram here.